About Khinalig

Khinalig is one of the oldest and highest continuously inhabited settlements in the Greater Caucasus and Europe, known for its historical and cultural importance. Its unique language, which forms its branch within the Nakh-Dagestani language family, is spoken only by the people from Khinalig and is distinct from Azerbaijani and the languages of neighbouring villages.

The village's isolated geography has helped preserve its traditions, including indigenous practices, oral storytelling, and ancestral customs. This isolation has also kept Khinalig mostly unaffected by imperialism and globalisation until recently.

There are three museums: one governmental and two initiated by the villagers. The villagers curate the museums by themselves, and there has been little to no government interference. In 2023, Khinalig gained UNESCO cultural heritage status.

Abstract

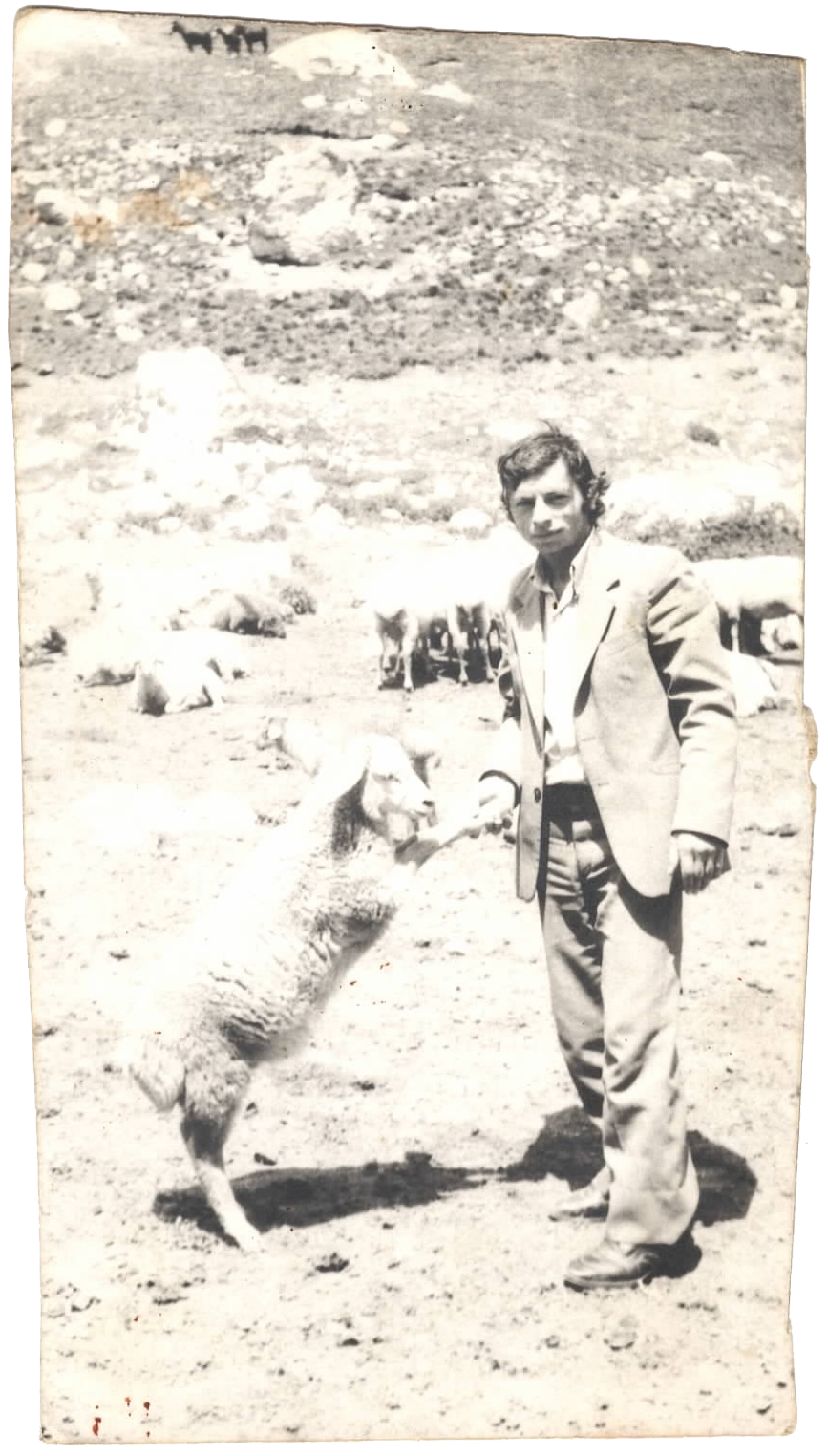

Homecoming is an artistic-ethnographic project about the heritage and my relationship to the village of Khinalig. Located in north Azerbaijan, Khinalig is home to an Indigenous minority that speaks a unique language. I, an artist of Khinalig origin, explore the nuances of digitalisation and institutionalisation and ask how a trained designer can help the community overcome these issues.

of Bayramgulu Bağirov

In Homecoming, I explore my relationship with the village of Khinalig, my ancestral home, through an artistic-ethnographic project that seeks to preserve its heritage and culture. Khinalig, a unique and isolated village in northern Azerbaijan, has a rich history and an indigenous language. My project combines digital archiving, collaborative publications, and artistic installations to capture and share the cultural narratives of Khinalig.

I ask how we might preserve living culture without reifying its forms and how to empower local voices in curatorial decisions traditionally made by external authorities. This project also attempts to reconnect with my heritage through artistic practice, reflecting on identity, belonging, and the complexities of cultural preservation in a globalised world. Through the method I call Homecoming, I aim to offer an alternative approach to heritage that respects local agency and keeps culture alive within its context.

Monograph on Khinalig

I have prepared a monograph presenting some aspects of the life and history of Khinalig. The format and layout of this monograph are appropriations of the Census of India village survey books, a format used by post-colonial government administration workers. However, I have interpreted the rigid format as a basis for creating an overview book of Khinalig, an introduction for those who wish to learn more about the village. Each section briefly describes aspects of Khinalig: history, geography, social life, beliefs and heritage. The publication relies heavily on oral history and uses a looser approach to references, deliberately moving away from the strictly academic approach to sourcing knowledge.

Book on Khinalig Language

The Book on Khinalig Language is a book that reads like a collage, covering the origin of the indigenous language, its relations with other languages in the region, and its transformations from an oral to a written form through digitisation and design. My main motivation in talking about language was to cover the design and accessibility problems that inevitably arise when language does not have a consistent script. I first conducted textual research, ranging from internet searches to reading articles, and then extracted quotes from research papers and articles to support my narrative. I interviewed some experts in the field of type design and discussed the nuances of digitising unique scripts and creating typefaces for endangered languages.

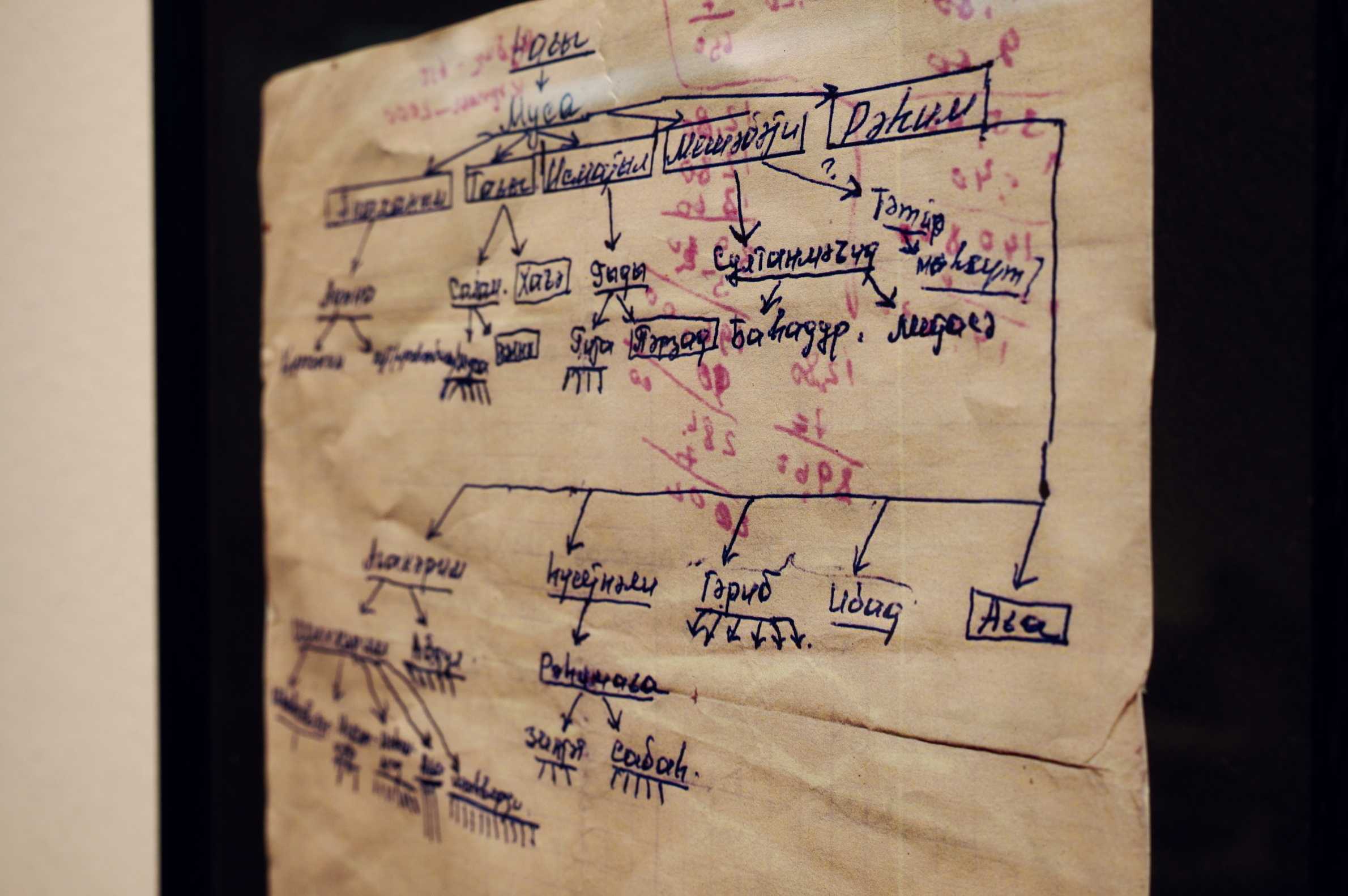

Publication based on researcher’s diary

During one of my travels to Khinalig, I found the diary of a villager who was composing the archaeological excursion hiking route. After his sudden death, relatives stored the diary in his family house but never read it. I deciphered, digitalized and translated the material in the diary and selected several excerpts. This work is a commentary on the information that gets lost in transliteration: the younger generations of Khinalig people cannot read the script their ancestors used to write their notes. The style of this book reflects the decay and fragility of ancestral knowledge.

Book on archaeological findings

A publication about the archaeological excavations in Khinalig and the archaeological findings found there. The findings are sorted into collections based on whom they belong or where they were found. This publication is a preliminary version of a catalogue of archaeological findings that will be published in the future.

Theoretical part of Master Thesis

A theoretical part of the Homecoming project, is a text that tries to contextualise, describe and problematise the methods used in the project. Designed as a booklet and printed on risograph. Contains the whole project documentation.

Installation

The installation was specifically created for the Master Thesis exhibition that took place from the 3rd until the 5th of April 2025. It has various parts linked to the project and includes many interactive pieces. Each of them is made of a different material but is united by one principle: the piece is not evident by itself and requires different ways of activation. Some pieces are publications, showcased in a special way, some contain photo or video material. Read more about the Homecoming installation and exhibition on the Digital Media Bremen website.

On Museums

Museum: an assembly of significant things, a tapestry of cultures, collaged by a hesitant curator who puts a golden horn next to an embroidered crown in front of a marble tomb. Visual contexts evaporate leaving only a dry exegesis, providing a reasonable meaning to lonely, kidnapped things.

Mwazulu Diyabanza, among other pan-African activists, is taking the artefacts that belong to his ancestors and culture from the museum and bringing them back to homeland. In the interview he says:

“When the Europeans arrived, the first bases they broke were cultural bases, now with this action we try to restore them.”

This act of decolonisation left a big impression on me and made me think about ways the museums are or can be made.

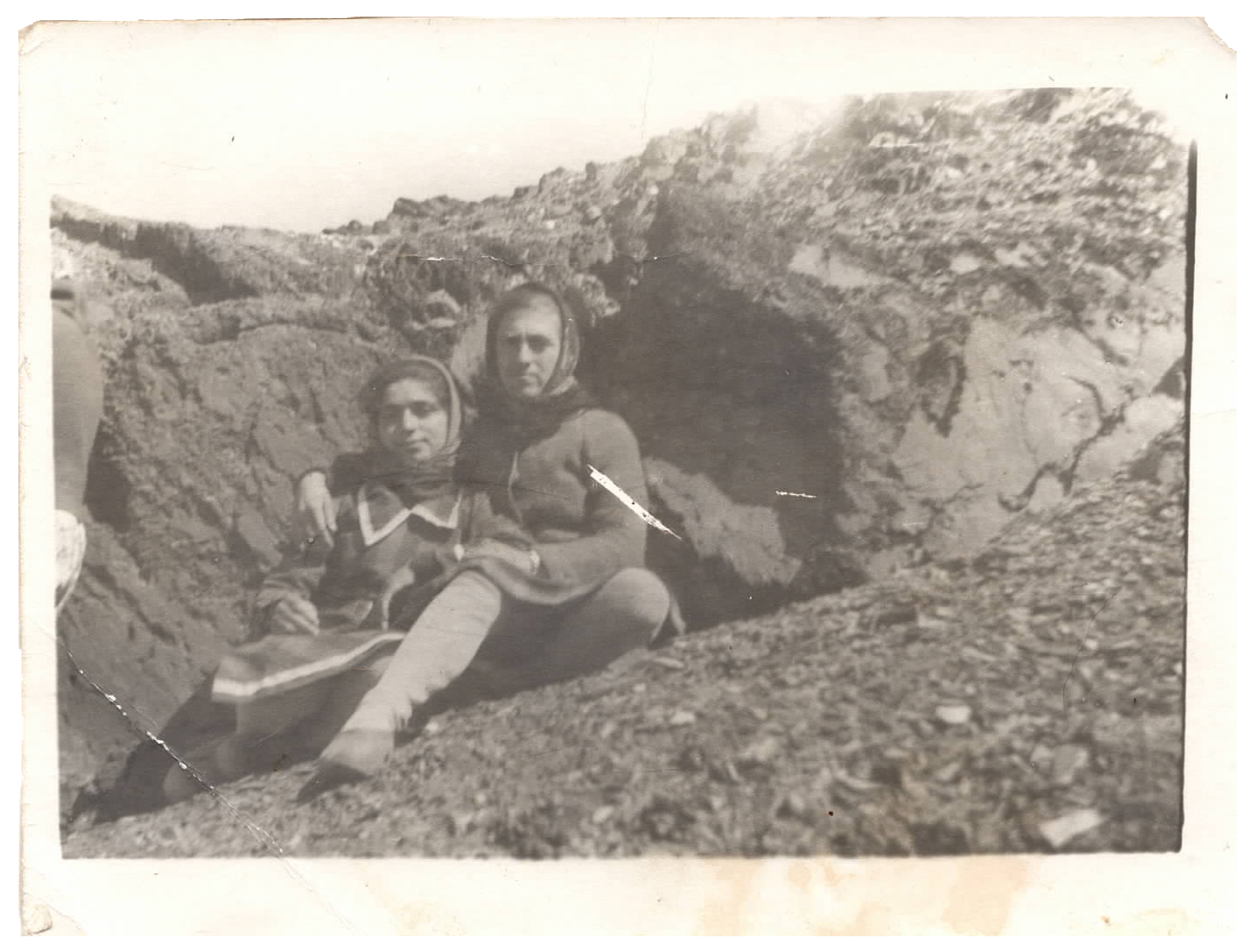

Khinalig, the village on the mountain was too isolated and remote for archaeologists and museologists so the first excavations started only around 2010. Nowadays there are three museums: one governmental and two initiated by the local residents. The villagers are curating these museums by themselves, so far there is little to no interference from the side of the government. It is not a white cube, you can touch and use some objects, there are unwritten stories that are told about the things exhibited, the museum, future of the village, archaeological excavations.

Home museum is especially precious: it is located in the living room of a hunter who has collected things in the mountains by himself throughout decades. You come in the living room, eat, drink tea, listen to him and look at the objects, take them in your hands and rotate them, feel their history not in an alienated manner but here, right in front of you, close to the place they were found at.

Now that the village is slowly gaining the attention of tourists and researchers, how can one preserve the local initiatives and curatorial decisions, and most importantly, keep the objects where they were found? Maybe it is possible to build an alternative environment for those who want to research, publish, and exhibit?